Wamkele Mene, secretary general of the African continental free trade area (AFCFTA) and NBSP

Author: John Muchira, line writer

Historically, Africa was consistent in the creation of a scheme for pursuing integration through major chief plans. Many remained only plans on paper due to poor implementation. A similar trend is announced to the African continental free trade area (AFCFTA), an agreement which was presented as the Holy Grail in the Revolution of Commerce, Investments and Economic Development.

On May 30, the continent marked the sixth anniversary of the signing of the AFCFTA agreement. Like many other treaties of magnitude, the AFCfta is at the risk of losing its appearance. Admittedly, only the Eritrea openly called the unnecessary agreement and chose to keep away. Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali were suspended after military boosts sparked strokes. Essentially, 45 countries of a total of 48 which ratified the agreement believes in the principles of the AFCFTA. In reality, it is as far as it goes – believing in the ideals of the agreement.

Africa Kiza, doctorate at the University Hamburg in Germany, captures the photo. “AFCFTA’s aspirations and ambitions are brilliant. The problem was to put the cart in front of the horse, ”he says. He explains that, in desperation, African leaders rushed in the signing of an “shell” of an agreement in the hope of resolving a mountain of obstacles along the way. Obviously, attacking obstacles in the midst of internal and external geopolitical and economic landscapes turns out to be Herculeans.

On the aspirations, the continent painted a pink painting. The first was the elevation of the AFCFTA at the top of the 2063 agenda, putting the agreement as one of the flagship projects. The expectation was that the agreement would be the ultimate solution in solving fundamental economic problems that hide the continent, namely low integration levels, excessive dependence on basic product exports and access to the limited market for African companies. By creating a single market for goods and services, the agreement would securely lay the foundations for the creation of a continental customs union. These are in particular the main conditions for the creation of the African Economic Community.

Stimulate intra-African trade

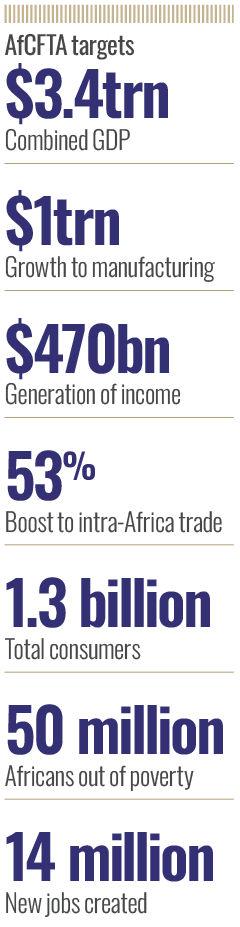

For AFCFTA, the objectives are clear, at least on paper. The primordial objective is the creation of a single market of 1.3 billion consumers with a combined gross domestic product of $ 3.4 billion. He has other advantages. The largest is to stimulate the intra -African trade of 53%, the growth of the manufacturing sector of $ 1 billion, generating income worth $ 470 billion, creating 14 million jobs and raising 50 million Africans – or 1.5% of the continent’s population – out of poverty.

The fact is that the future of Africa is imagined through frameworks imported from elsewhere

Six years later, the realities of putting the cart before the horse are blatant, with part of the absurdity. An example is the fact that the AFCFTA secretariat, which was created in 2020, continues to be funded by the German development agency Giz, which also finances negotiations in addition to providing technical assistance. Thanks to Giz, progress has been made on the legal construction of the agreement reducing the rules of origin for certain sectors, the dispute settlement mechanism and digital trade, among others.

Giz’s support cannot be underestimated. However, he exhibited Africa on two fronts, one being administrative ineffectiveness and the other being the tendency to cling to the dependence of “the economy of institutions borrowed”. “The fact is that the future of Africa is imagined through imported executives elsewhere,” observes Professor Dunia Zongwe, an associate professor of law at the University of Namibia. He adds that the situation is complicated by deep historical ideological tensions between the neoliberal and pan -Africanist doctrines of Africa who have catalyzed the curse of the continent for decades.

Larger negotiation levels than expected

The impact was a slow implementation of the AFCFTA. Before signing the agreement, the total official trade of the continent totaled 12 and 18%. In 2022, the guided commercial initiative was launched to launch real trading under the AFCFTA. However, intra-African trade remains less than 20%. Last year, trade between African countries increased by 7.7% to 208 billion dollars, according to the African Export-Wirelessness Bank. The value addition level remains dull, with total export value at $ 682 billion and imports $ 719 billion.

At the end of 2024, 31 countries out of the 45 had initiated a certain form of trade, although completely negligible. The growing number, a significant increase compared to seven in 2023, coupled by the adoption of three new protocols on investments, intellectual property and competition, are a demonstration that Africa is committed to strengthening the momentum to deepen the objectives of the framework. The ultimate hope is to increase intra-African trade to 53%, putting it equally with other continents where intra-trade is booming. In Europe, it amounts to 68%, in Asia at 59%and North America at 51%.

“The fruits of the commercial block are low, but they will gradually mature according to the implementation of the agreement,” observes Professor Zongwe. He adds that, so far, the continent has occurs lamentable, with a low rate of implementation of the policy of only seven percent. Even the African Union (AU), the highest director, has admitted that so far, it was a case of failures rather than blows on AFCFTA.

A number of obstacles to overcome

Reality emerges that to make AFCFTA work and for Africa to be fully realized, the difficult task lies in the fight against the myriad of structural, logistical, political, economic and other obstacles confronted with the agreement.

Address these challenges is mainly slippery because most countries, especially the least developed, have trampled on their development by looking inward as opposed to external integration. Most indicate that AFCFTA is finally designed to benefit from major economies that desperately need new markets for their goods and services. For them (small savings), the agreement is a continuation of the profits as opposed to equality.

Kiza gives practical examples. An American citizen has the luxury of traveling in 24 African countries without a visa. For a Ugandan national, the same goes for only nine countries. This desolate situation was described by the deliberate refusal by the countries to ratify the AU protocol on the free movement of people. Only four countries have ratified the protocol.

It gets worse. Despite being a large cocoa producer, only second behind Ivory Coast and counting a world quarter, Ghana chocolate exports to South Africa attract 30% of prices. For Switzerland, chocolate exports to South Africa do not attract any price.

If this is not absurd enough for an integration of desire from the continent, the economic disparity gives a context. Burundi, whose economy is worth $ 3 billion, is expected to open 97% of its market. The same goes for Nigeria, with an economy of $ 487 billion.

“The idea that the liberalization and the elimination of prices before strengthening the capacity of small nations will automatically increase trade is wrong,” notes Kiza. He adds that the continent must apply brakes on the political opportunity and focus on the fundamental blocks that will operate AFCFTA.

In fact, the inability of the various blocks of the regional economic community would flourish, although it is the foundations on which the AFCFTA presents itself, offers vital lessons. The Eastern African Community (EAC), for example, is disintegrated due to political and economic rivalry.

Expensive barriers on the way

The list of catalysts that require fixation is the enigma infrastructure. Without a doubt, mediocre transport networks, inadequate logistics systems and ineffective border procedures are enormous obstacles to trade. Physical barriers make it more expensive for African companies to negotiate each other with each other than with partners outside the continent. It is not difficult to see why. In sea trade, for example, 98% of sea companies belong abroad. For them, it is economic logical to flood Africa with foreign goods which have trouble filling a container of goods produced on the continent. The challenge extends to rail transport, where low investments have increased insignificant connectivity to only 0.1%.

Although poor connectivity is a major factor in high costs of goods produced in Africa, non -tariff obstacles (NTB) have become trade toys in the pursuit of political interests and protectionism. Subsidies, import prohibitions, complex customs procedures, regulatory inconsistencies, corruption and other administrative obstacles continue to hinder cross -border trade. At the EAC, for example, the direct cost of the NTB was estimated at $ 17 million in 2023. Since AFCTA has no ban on subsidies, which, with cases of spill, is among the most disputed problems before the World Trade Organization, this means that Africa can expect NTB to continue to undermine fair competition.

On prices, the continent has structured a gradual reduction over a period of 15 years, the ultimate objective being to liberalize 97% of goods by 2034. “Some countries are reluctant to fully open their markets because they fear losing income from the reduction of prices or negative effects of more rigid competition on national industries,” explains Professor Zongwe. He adds that fear comes from the fact that, for most countries, production structures are largely similar.

As an attenuation of the attenuation of the reduction of pain relievers on the effects of the reduction in prices, the continent has a commercial adjustment fund of $ 10 billion in place. In addition to alleviating potential negative impacts, such as pricing income losses and market disturbances, the fund will also be used to process infrastructure deficits and the bottlenecks of the supply chain. This is essential because Africa understands that for AFCfta to have a semblance of success, the continent must detach itself from the colonial yoke of export of raw materials and basic products and to import finished products. Essentially, the addition of value must become the new mantra.