By Angelique Coutantou, Forrest Crelin and Edward McAllister

ATHENS/PARIS (Reuters) – Rent has always been high for Athens restaurant owner Christos Kapetanakis, but now he faces what he calls “second rent” as rising electricity bills cut into profits and force him to raise prices.

Kapetanakis pays between 3,000 and 3,800 euros ($3,083-3,905) a month for electricity, a 40% increase since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 and triggered Europe’s energy crisis. It was 3% of the monthly turnover, and now it is more than 15%.

“Continuous price increases, especially in the tourism sector… will lead Greece to become less competitive compared to other Mediterranean countries,” he said from a restaurant in the historic Plaka district.

Its plight has been echoed across the continent since the war in Ukraine cut off Russian pipeline gas supplies to Europe, forcing countries such as Greece to seek more expensive alternatives.

But South-East Europe felt the impact much more than North-West. Experts say this will only widen as winter approaches and have a devastating impact on economic growth.

Wholesale electricity in Greece and Italy was 12 times higher in August than in Scandinavia and even other southern European countries experiencing hot weather.

the highest in the EU

From 2021, Greece has spent €11 billion on energy subsidies to protect consumers. In 2022, spending was 5.3% of GDP – far higher in the EU and more than double that of second-place Italy, according to Enerdata, a France-based energy consultancy.

Despite Athens’ efforts to protect citizens from rising energy costs, the situation has exacerbated Greece’s cost-of-living crisis since the 2009-18 debt crisis that slashed wages, pensions and investment in power generation and transport.

“Increased energy prices and negative impact on GDP is a tautology,” says Nikos Maginas, senior economist at the National Bank of Greece.

“Increased prices will have a negative impact on household consumption and the cost structure of industry, airlines and shipping.”

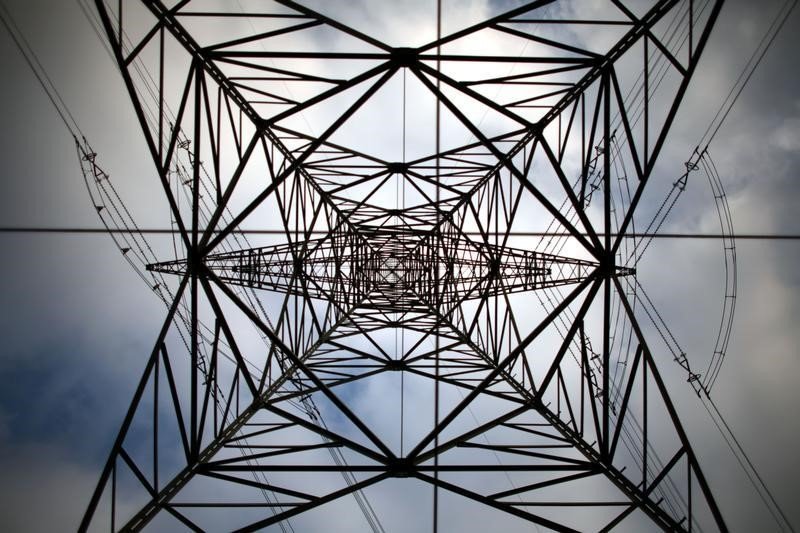

Much of the contrast between Southeast Europe and its neighbors comes down to investment. While the Northeast has electricity and gas lines that allow easy energy transfers between nations, as well as a strong mix of renewable sources, much of Southeast Europe is fragmented and isolated.

Electricity storage, which is becoming increasingly important in northern European countries, does not exist in parts of the southeast. Germany has 1,668 megawatts (MW) of large-scale storage capacity, second only to mainland Greece, according to Edinburgh-based energy consultancy LCP Delta.

“Southeastern Europe and the Balkans lack (electricity) interconnection. When there is a shortage of electricity and renewable energy production is low, they struggle to import the required volumes,” said Henning Glostein, Head of Energy, Climate and Resources, Eurasia Group. .

In contrast, Spain’s renewable energy output has grown over the past decade, thanks in part to EU funding. It generated nearly 60% of its electricity from renewable energy in the first half of this year, up from 51% a year earlier.

“If you don’t invest, energy prices will stay high,” Glostein said.

more to do

Europe’s energy grid has been a great success in many ways. In 2022, France increased its imports from Germany as nuclear power output declined. When Russian gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine were cut off last week, the impact on prices eased as the bloc found alternatives.

But for some, more needs to be done. After Greece’s electricity prices rose last summer, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis wrote to the European Commission demanding a solution to the “unacceptable” differences in electricity costs across Europe.

Greece is not alone. Much of the Balkans is dependent on fossil fuels and the regional energy system is weak. Last June, blackouts occurred in Montenegro, Bosnia, Albania and Croatia when the grid was overwhelmed by the need for air conditioning during the heatwave.

Kosovo, which generates more than 90% of its energy from coal, has been trying to catch up with the rest of Europe by installing more renewable energy.

In December, it launched an auction to install 100 MW of wind capacity. But the World Bank estimates it needs 100 times that – at least 10 gigawatts of new capacity – to reach its goal of eliminating coal use by 2050. The transition is expected to cost Kosovo 4.5 billion euros, staggering for a small economy.

Without sufficient cross-border integration or storage, sometimes there is too much power for one market, forcing manufacturers to limit supply.

“If the goal is more specifically to lower prices, the easiest way to do that is to increase the penetration of renewable energy or nuclear energy,” said Fabian Ronningen, an analyst at consultancy Rystad Energy.

Although Greece has no nuclear plants, Aristotle Ayvaliotis, secretary general of the energy ministry, is upbeat, noting that renewable energy output is increasing, two new gas-fired power plants will come online this year and battery storage will be built by 2028. .

Plans also call for upgrading electricity connections with Italy, Albania and Turkey by 2031 at a cost of around 750 million euros.

“Wholesale prices will gradually come down … and that will definitely be passed on to consumers at some point,” Ayvaliotis told Reuters.

Greek consumers are not convinced. Taxiarchis Fekas, who lives on the outskirts of Athens, struggles to pay school fees and allowances for her three children because the electricity bills are so high.

She encourages her children to cut back on laptop and tablet use to save energy — a tough call for young children who are glued to their devices.

“We are on the verge of becoming a financially strapped family,” he said. “The government should pay attention.

($1 = 0.9730 EUR)