A mining operation in Indonesia, credit: Tom Fisk and Nbsp

At the beginning of 2025, the private credit market exceeded $ 3 billion in management assets (AUM) and was one of the “fastest growth segments in the financial system in the past 15 years”, according to an article in McKinsey. This dazzling elevation has seen the industry develop a factor of 10 between 2009 and 2023, adding $ 1 billion in the last 18 months. The main cause? Relatively banks. The traditional bank was forced to withdraw following the global financial crisis in 2007-2008, moving away from traditional loans and exceeding more on debt markets and parallel banking services.

Since then, of course, we have attended a global economic uncertainty in the form of the pandemic, the Russian-Ukraine war, the continuous conflict in the Middle East and more recently, whenever the American president leaves a comment on social networks or sets off in front of a camera. According to Basel III, market volatility, but also by tightening regulatory pressure, in particular the end of the Basel III parts proposals, which would force banks to increase their capital reserves in a range of loan zones and to introduce liquidity rules that would reduce the appetite of banks for longer -term loans, according to McKinsey.

With banks sensitive to market shocks and hampered by the policy, private credit has moved, a recent EY report believing that “Europe represents around 30% of the private credit market”. There are many key engines for growth across the continent, including investment in infrastructure and energy. Private credit should play a leading role in the global green energy transition “with estimates suggesting that between $ 100 and $ 300 billion will be necessary by 2050,” said EY. Private credit now seems to be a pillar of the financial landscape, a counterattack champion in time of economic turbulence, but what happens when private capital meets geopolitically unstable jurisdictions, and how the financial markets are not exposed that they cannot see?

Private credit explosion

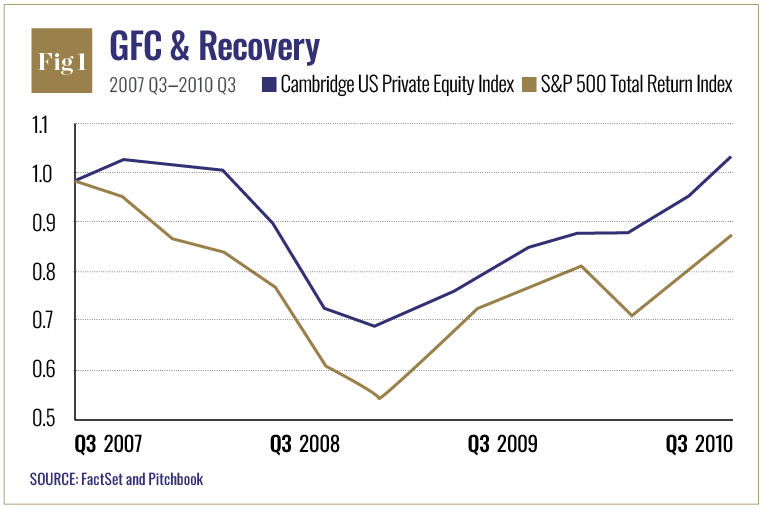

Post-GFC, the failure and the quasi-Faille of several banks “too large to fail” have helped to trigger the great recession, the most serious slowdown in the world economy since the Great Depression. Millions of people have lost their homes, their savings and their work. Although the economic slowdown has had an effect on private credit, the data show that “historically, investment capital portfolios have generally experienced lower peak decisions than public procurement”, according to a study on the return models during the economic slowdowns of Neuburger Berman (See Fig 1). While banks were to limit their exhibition, the private landscape of the agreement rebounded during the last part of the recession, in 2009. The post-GFC environment was the first real stress test of Private Equity and it succeeded, although in a close way. A recent investment capital report during the major recession explains how the leading capital fund managers have failed to “acquire high-quality assets at high discounts” despite the sharp increase in agreements.

Analysts attribute the historic rise of private credit with three key characteristics. In comparison striking with banks, the EP has better access to capital and more freedom to deploy it, allowing it to increase market share and experience higher growth in the crisis. Most global funds also have active management with heavier emphasis on value creation. This has provided decisive support to funds in order to develop new capacities and conduct transformation projects. Finally, the investment capital is relatively illicid, which means that during economic slowdowns, it can help isolate investors from the sale of panic, which generally includes higher losses. With higher yields, tailor -made conditions and less surveillance, the call for private credit cannot be overestimated.

The last 15 years have seen a private credit explode, but buried in this success are reasons of caution. The most obvious is the risk of illiquidity. Although useful during a slowdown, the ability to withdraw money from an investment quickly is generally considered a good thing. Coupled with the fact that geopolitical instability is rarely at an adequate price, cracks could quickly form.

Compared to market risks, geopolitical risks are incredibly difficult to cover. The effects of political instability, commercial disputes, war, cyber attacks, climate change and natural disasters can be sudden and severe.

Shortly before the invasion of Ukraine Russia, Horizon Capital, the largest investment capital group in Ukraine, had just launched its fourth flagship fund. Sarah de St Croix, head of private funds from the law firm Stephenson Harwood, commented the importance of having arrangements in place to help managers financed to respond to geopolitical developments. In this case, “affected managers were able to count on their generic right to force an investor of the fund where their participation continues to viose the law or the regulations.” Even if these clauses were written without a clear meaning when they could be necessary, the funds were able to “manage the problem of having an investor sanctioned in a common swimming pool following the general taxation of sanctions to the Russians in 2022.”

Private credit became global after the GFC, at a time when geopolitical risk was not in mind. Weijian Shan, executive president and co-founder of the investment company PAG, says: “Geopolitical risks are very real.

Resource nationalism

And this is quite strongly concentrated if we consider things such as the risks of sanctions, political disorders or local capital controls trapping foreign investments, or populist governments reversing the protections of investors.

The last 15 years have seen a private credit explode, but hidden in its success are reasons of concern

Indonesia, which produces 37% of world nickel and is a large world exporter of coal, palm oil, copper, gold and other minerals, has participated in a program of nationalism of decade resources. The Indonesia program has coincided with the high demand from China and, as Dr. Eve Warburton notes of the Australian National University: “During this same period, the Indonesian government has entered more and more nationalist policies – new divestment obligations for foreign minors, the ban on export of gross minerals, new requirements of strict local content and restrictions on foreign investments in oil and the gas sector. ” In addition and perhaps the most revealing, “the observers noted an increase in judicial cases and a popular mobilization against foreign companies”. This is particularly important given the essential role of nickel in the batteries of electric vehicles and the storage of renewable energies, placing Indonesia at the heart of the global energy transition.

Weigh up the risks

The private credit market must navigate considerable obstacles if it is a question of avoiding becoming a victim of its own success. Rapid growth has increased funds more and more in new niches, often on emerging and border markets where yield – and risk – is the highest.

In geopolitical influence and peace, a report from the Institute for Economy and Peace, they declare that “geopolitical risks today exceed the levels observed during the Cold War, trained by increased military spending, blocked the efforts of nuclear disarmament and a reduced role for multilateral institutions like the United Nations.” At the same time, we are witnessing active wars in Ukraine and Gaza, American-Chinese decoupling, the increase in political instability and polarization, the spread of disinformation and an increase in the use of cross-border sanctions and capital controls.

The risk of financial contagion is also a concern for industry. Anyone in charge of private credit – think of pension funds, sovereign funds or insurers – is increasingly their capital linked to private opaque and illiquid offers.

Investors run the risk of being exposed to losses for which they did not provide for neither planned nor are properly evaluated. Any crisis on the private credit market could have a significant training effect with the wider financial system. While private credit funds extend more in higher risk courts to meet performance expectations, the potential for sudden and serious losses increases considerably.

The success of Private Credit was built on access to capital, flexibility and the possibility of going where the banks will not. But these advantages can quickly become responsibilities in an unstable world. While geopolitical risks increase, private credit managers and their investors must rethink the way they assess the modern rapidly evolving landscape. The next market crisis may not start with Wall Street or on bond markets – but in a foreign ministry, a war room or a populist parliament. Private credit must be ready.