Despite a succession of shocks since 2020, the world economy has remarkably resistant – so far. But the margin of error is down. Total world debt is now almost 25% higher than the day before the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was already at a record level. This overhang could undermine the ability of all savings to protect itself from the last shock: higher trade rates.

Although the debt is crucial to stimulate economic growth, it must be understood as a deferred form of taxation. By borrowing rather than taxation, governments can make long -term investments that will benefit future taxpayers without withdrawing the current generation; Or they can support national growth and income during an economic emergency, when hiking taxes would only deepen the slowdown. Finally, however, the Piper must be paid, and if the national income does not increase more quickly than the cost of the loan, the taxes must be increased to reimburse the debt. Persistent debt is therefore an obstacle to economic progress. This barrier has rarely been higher. Over the past 15 years, developing countries have hung on debt, which they have accumulated on a record clip: six percentage points of GDP per year, on average. These accumulations of rapid debts often end in tears. Indeed, the chances that they trigger a financial crisis are around 50 to 50.

In addition, this particular increase was punctuated by the fastest increase in interest rates in four decades. Borrowing costs have doubled for half of all developing savings, net interest costs as share of public income from less than nine percent in 2007 to around 20% in 2024. This alone is a crisis. Although the world has so far managed to dodge a “systemic” financial crisis in the 2008-2009 variety, too many development savings are now in a loop of misfortune. To respond to their debts, many reduce investments in education, health care and the infrastructure they need to ensure future growth.

Future Global WorkForce

This is particularly true for the 78 poor countries which are eligible for borrowing from the International Development Association of the World Bank. These countries are home to a quarter of humanity, representing a large branch of 1.2 billion young people who will enter the world workforce over the next 10 to 15 years. However, decision -makers around the world have chosen to try fate. In another triumph of hope over experience, they bet that global growth will accelerate – and that interest rates will drop – just enough to defuse the debt bomb.

The world cannot afford another decade of drift and denial with regard to debt

Such passivity is understandable. It was extremely difficult to conceive of a 21st century system capable of ensuring the sustainability of global debt and rapid restructuring of debt for countries that need it. In the absence of such a system, the progress that occurred has been too slow to avoid the increase in the dangers of debt. But the world cannot afford another decade of drift and denial with regard to debt.

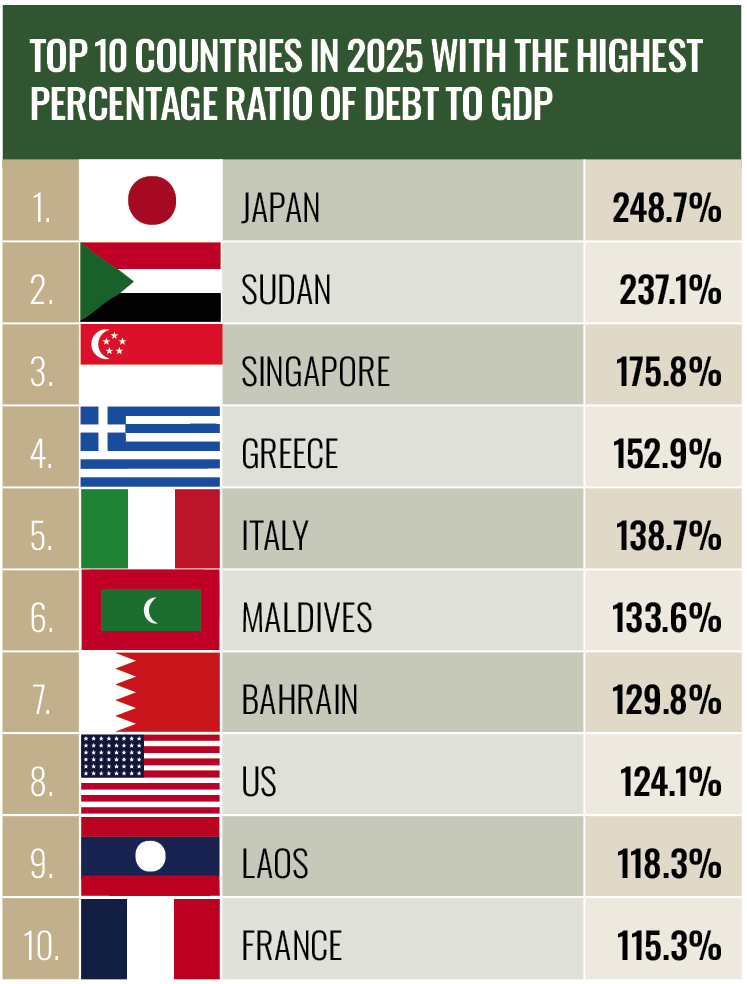

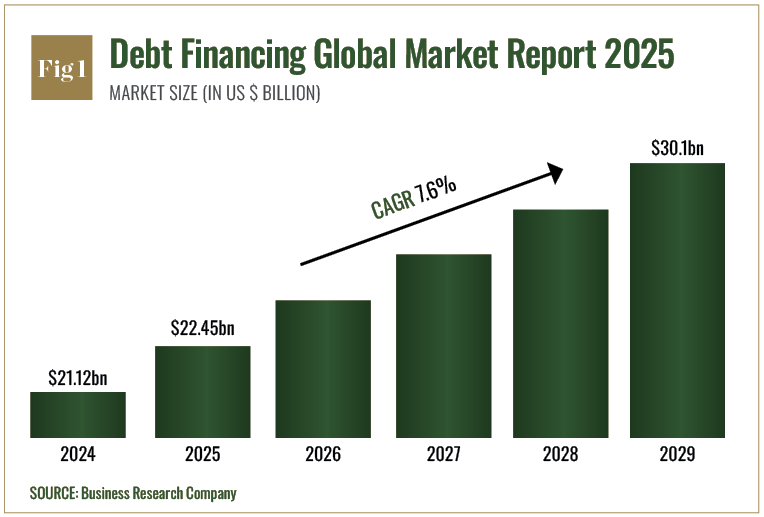

As part of current policies, global growth does not accelerate as soon as possible, which means that sovereign debt / GDP ratios are likely to climb for the rest of this decade (See Fig 1).

Dark predictions predicted

Today’s trade wars and the record levels of policies of policies have only aggravated the perspectives. At the beginning of 2025, consensual forecasts among economists were predicted at 2.6% global growth this year. This number is now down to 2.2% – almost a third of the average that prevailed in the 2010s. Interest rates do not drop either. In advanced savings, interest rates set by central banks are expected to average 3.4% this year and next year, more than five times the annual average between 2010 and 2019. This will worsen the difficulties of developing economies. At a time of rare public resources, it will take a total mobilization of private capital to stimulate growth and development over the next five years. But it is unlikely that foreign private capital will occur in very indebted economies with low growth prospects.

Private investors will properly assume that economic growth gains will simply be taxed to repay the debt. Thus, the reduction in debt should be the top priority for the development of economies with persistently high debt / GDP ratios. But we also need a clear vision of broader problems: the global device to assess the sustainability of a country’s debt must be improved urgently. The current system is too fast to decide that countries simply need loans to mitigate them, while most low -income countries are in fact insolvent and will need debt radiation. Governments will also have to abandon the habit of borrowing from national creditors; The increase in interior debt is to strangle the initiative of the national private sector.

The question of prices

After reducing debt, the next priority is to accelerate growth. It is stupid to claim that growth will return as if by magic. Policies that hinder trade and investment – such as rates and non -tariff barriers – should be canceled as soon as possible. For many development savings, the reduction of prices also with regard to all trade partners could be the fastest way to restore growth. Development savings also have a lot to gain by promoting a regulatory environment more favorable to investments. And these gains can be used to give national attention to development, in particular by increasing investments in health, education and infrastructure.

The current system is too fast to decide that countries simply need loans to mitigate them

As the proverb says, when you are in a hole, it is wise to stop digging. An era of extraordinarily low interest rate has encouraged too many countries to pass far beyond their means. A series of disasters – both natural and artificial – have prevented them from doing something else in the past five years. But caution is now essential. Governments should return to previous standards on what constitutes excessive sovereign debt. Call that the maximum 40-60: 40% of GDP for low-income savings, 60% for high income savings, with everyone between the two.